Artist in Residence at Michigan Biological Stations - Summer 2023

What are your plant stories?

Through sharing stories of land, I led scientists in a collaborative art project that connected art, science, and identity.

Collaborative cyanotype tapestry at the KBS Bird Sanctuary.

In 2023, I was joint artist in residence at two biological stations in Michigan, the University of Michigan Biological Station (UMBS) and the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station’s (KBS) Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) site. During my residencies, I led workshops that explored the intersection of culture, identity, and colonialism on the community ecology of Michigan.

In collaboration with research faculty, undergraduate students, and non-academic community members, we created a series of tapestries using a cyanotype photographic technique. These cyanotypes were displayed at art-science exhibitions, including large cyanotype tapestries which are on permanent exhibition at both biological stations.

Project statement

Growing up, the best day of the year was in late April. After nearly six months of winter in Traverse City, Michigan, the snow would melt, chartreuse leaves would pop out of their buds, fiddlehead ferns, trillium flowers, and wild garlic could come out of the ground. Soon, the scent of cherry blossoms would hang heavy in the air and I’d drive with my windows down through the rolling hills of cherry and apple orchards on my way home from school. I could see the turquoise Grand Traverse Bay, which forms a microclimate buffered by Lake Michigan, and is perfect for growing fruit.

Those of us who had the privilege of growing up in the rural Midwest know that it’s like to feel the land. We celebrate its beauty and its bounty -- we know how to fry foraged morel mushrooms in butter and that the best dessert is maple syrup on fresh snow. But we also feel the land when ecological violence becomes human violence. I felt violence on the landscape when I stepped into Hartwick Pines, the only old-growth forest left in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. I felt for those trees, who had lost all their brethren when the entire lower peninsula of Michigan was clear-cut in the late 1800s. I had lost brethren too, growing up as a Chinese adoptee in a sea of white faces. I felt violence on the land when I heard others struggle to pronounce Peshawbestown and Sault Ste. Marie and Kalamazoo, reckoning with our history of immigration and colonial violence with my present experience. I felt the land when my loved ones were diagnosed with cancer and I learned that groundwater contamination not only in cities like Flint, but even my rural community, could turn tap water undrinkable.

The Midwest is a land rich with biodiversity, history, and care. Our stories of land are Indigenous, they’re Black, they’re stories of immigrants from Eastern Europe and Latin America. They’re urban stories just as much as they are rural stories. They’re stories of resilience and regrowth for many organisms, not just humans.

As a PhD ecologist and professional artist, I blend stories of land, ecology, and identity through a community-centered art practice. I grew up in Traverse City and pursued research at the University of Michigan Biological Station as an undergraduate. After finishing my PhD in Biology at Stanford University, I returned to Northern Michigan to celebrate its rich cultural and ecological history. Blending art with community activism that centers social justice, this residency celebrated the rich science and art knowledge at two biological stations in Michigan. Through collaborative art/science workshops, I centered personal stories of Northern Michigan through stories of land.

What is a cyanotype?

I chose to explore this intersection between science, art, and identity using an old photography technique, cyanotype. The cyanotype printing method uses two chemicals that react upon exposure to UVA radiation to produce a cyan-blue print.

Cyanotypes were originally used for scientific purposes. In the 1840s, British botanist Anna Atkins recorded the plants she collected using cyanotypes. Atkins published her plant cyanotypes in a series of books. Today, her books are considered by many to be the first illustrated with photographs, and she is often cited as the first woman photographer. Cyanotypes were also used to make engineering prints, originating the term “blueprint.”

After the advent of modern cameras, cyanotypes have become a popular tool for artists. The photosensitive ink mixture can be painted into paper, cloth, and a variety of other materials to produce striking blue prints.

Plant stories

At the beginning of the workshop, participant scientist-artists sat in a circle and shared plant stories. These stories connected their histories, cultures, and lived experiences to their relationship with land and plants.

Think about a plant that holds special meaning to you, family, or community. It could be a plant that you grew up with, one that reminds you of home, or one that has cultural significance. Share a story about your connection to this plant and how it relates to your identity and connection to where you are from.

Powerful stories were shared. From the tulip festival in Holland Michigan, to bright-burning birch at summer camp, to urban gardens growing a tiny cucumber that looks like a melon, we connected as a group through our love of plants and our stories about the environment. One young participant shared how their parents planted a tree when they were born and now the tree was taller than them!

Foraging for plants

Next, each person collected local plants to represent their story. On a quiet walk, participants gathered flowers, grasses, leaves, and sometimes insects! During some workshops, scientists brought specimens to include in the cyanotypes such as pinned insects or pressed herbarium plants. During a workshop at the Kellogg Bird Sanctuary, docents shared feathers with us to include in our cyanotypes.

Making the cyanotypes

Plants were quickly laid out on cyanotype color-changing paper in the sun to expose the light-sensitive chemicals. Exposed prints were fixed using a water bath or washed in the lake.

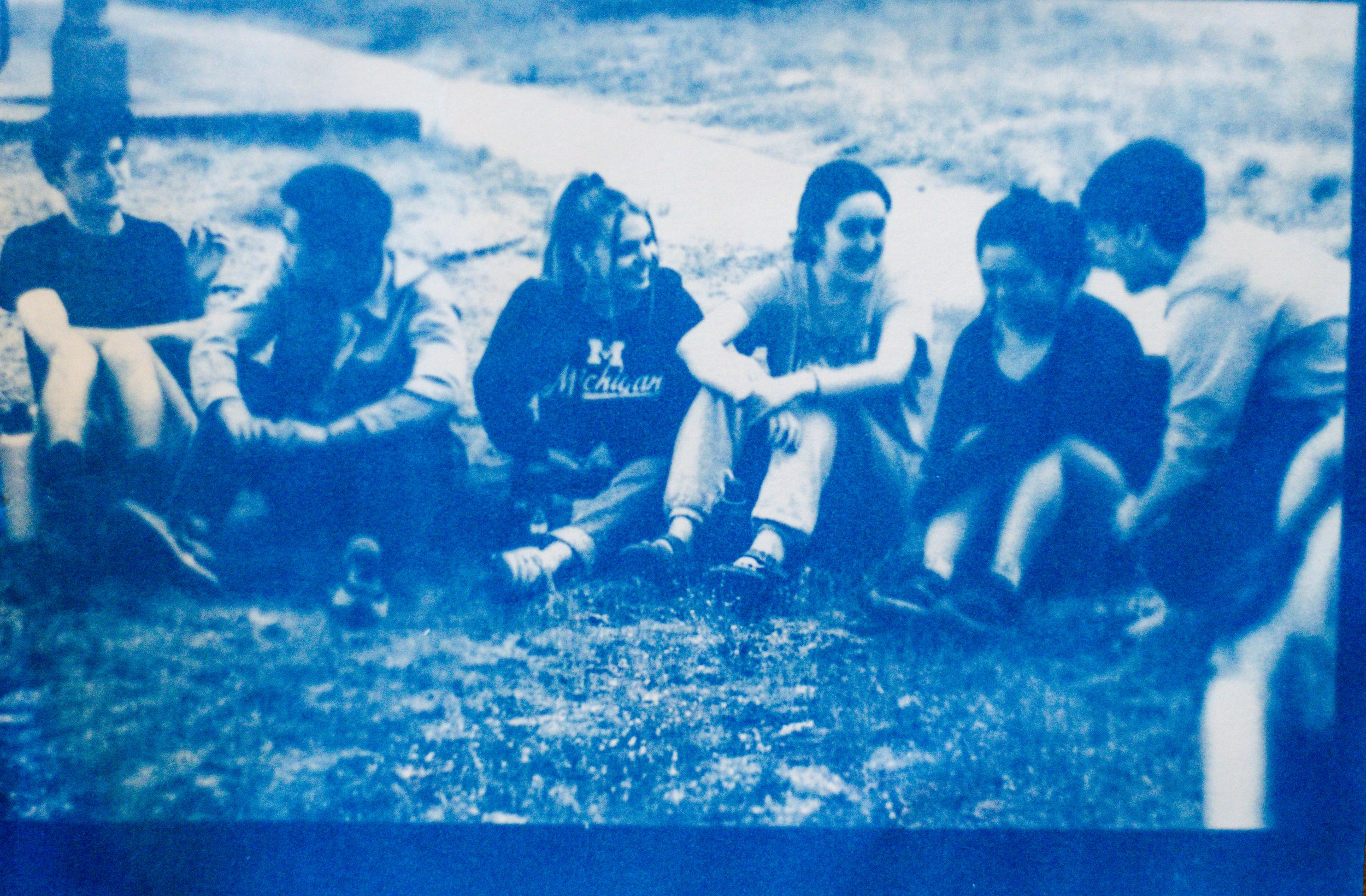

As a group, we also made large collaborative cyanotype tapestries. The color-changing chemicals were painted onto large watercolor paper sheets in a darkroom. Each group placed their plant materials on these large tapestries to document the collective plant stories. These large tapestries were then washed in the lake and hung to dry.

Final storytelling

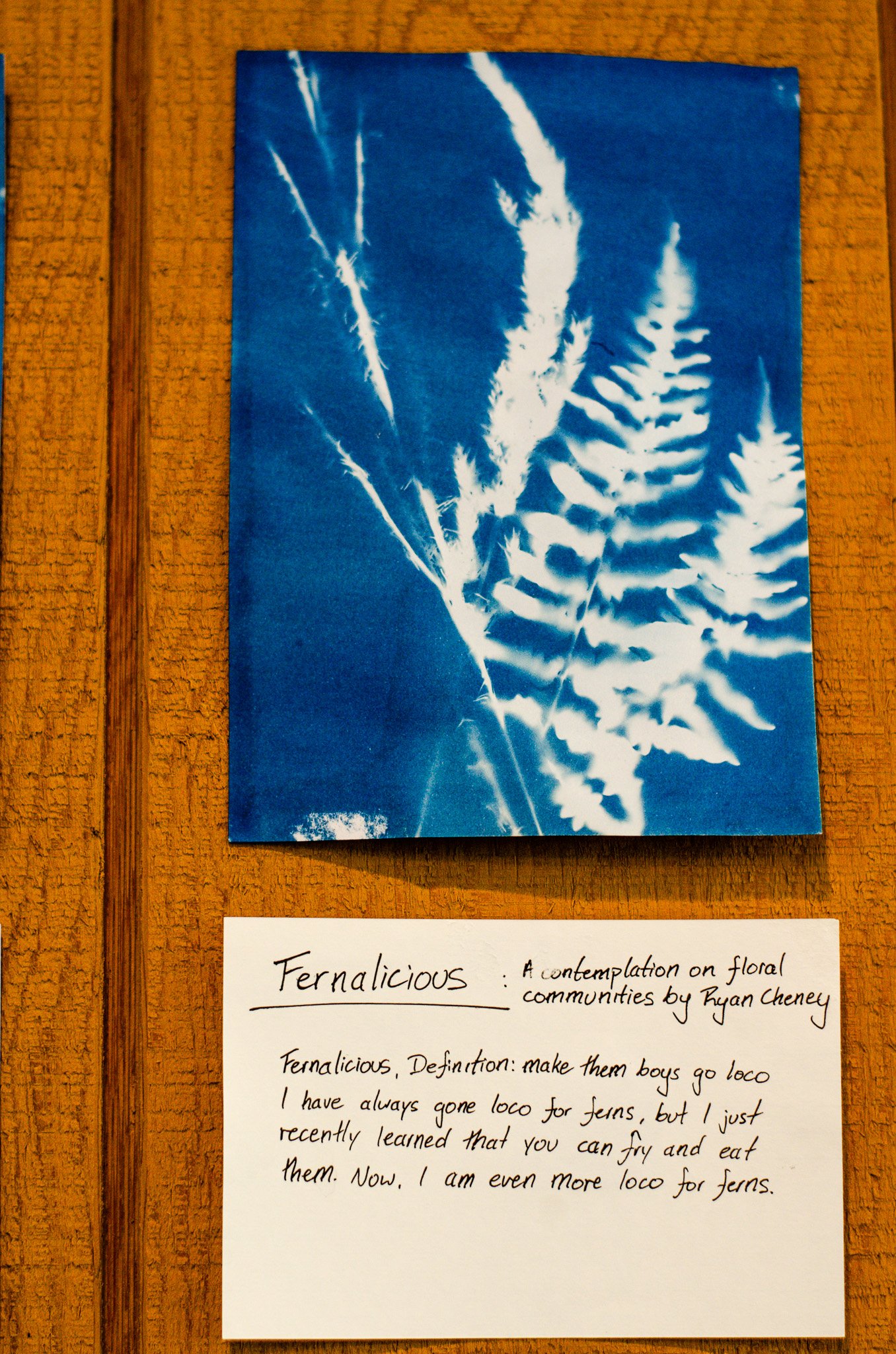

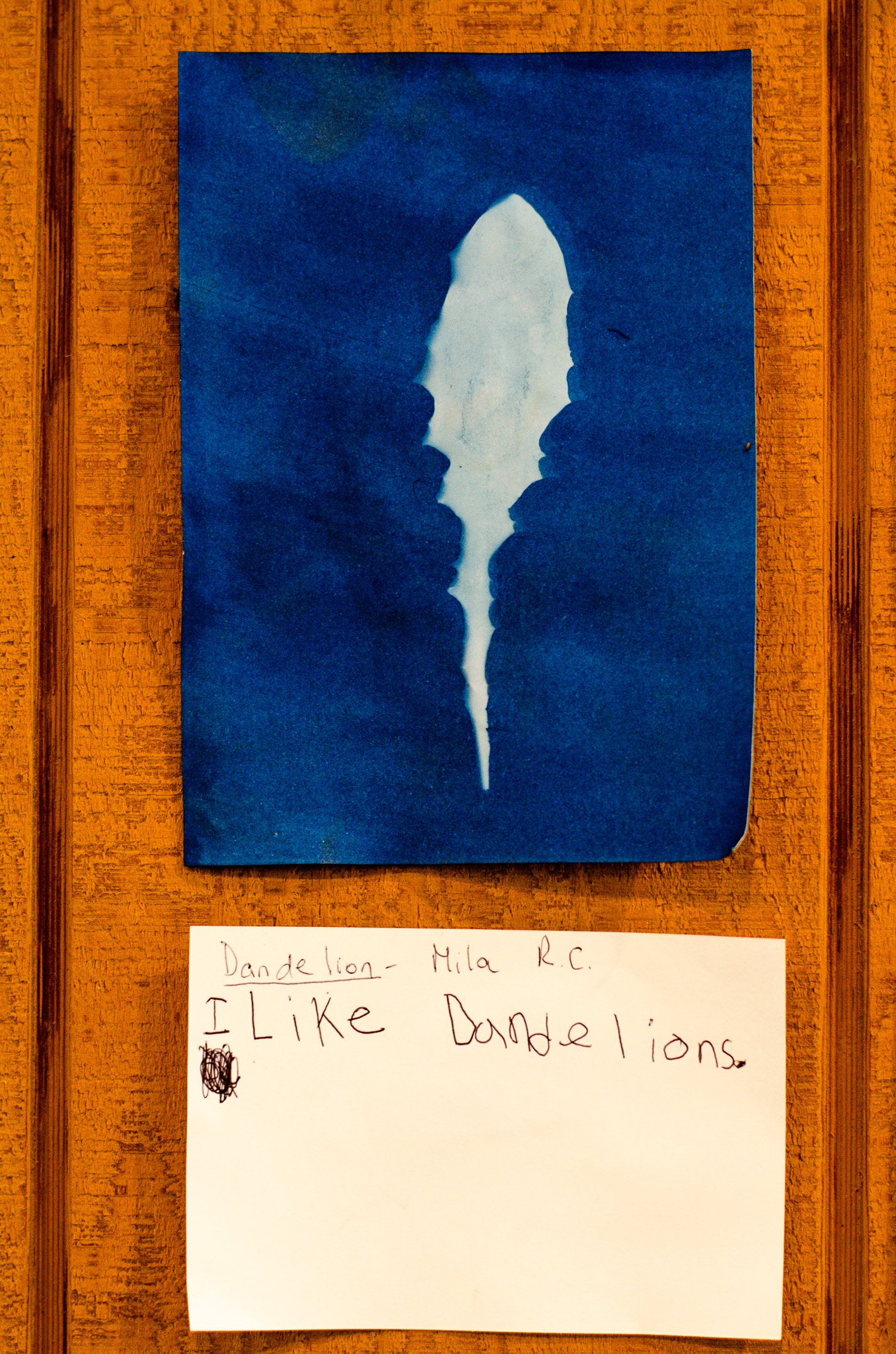

Each participant wrote their plant story as an artist statement with their cyanotype. The stories and reflections were beautiful.

You can view some cyanotypes and their stories below (click on each piece to reveal the story).

Exhibition

Individual cyanotypes with artist statements and the group cyanotypes were exhibited at each site. I also created “process cyanotypes” using digital images laserjet printed onto transparencies. These transparencies were used to create photograph-like cyanotypes of each workshop. During one day without sun, I used a DNA transilluminator to create these transparency cyanotypes!

At UMBS, the exhibition was held in the communal dining hall. As people enjoyed their meals, they perused the cyanotypes created by their colleagues, friends, and family. This exhibition included a few additional elements, including cyanotypes created previously by GLACE student Homayra Adiba and several cyanotypes created from student-created art/science nests. The three cyanotypes created by students, faculty, staff, and their families at are on permanent display in the UMBS dining hall.

At KBS, one workshop was held for researchers. The cyanotype created at this workshop is on permanent display in the KBS lecture hall and was exhibited during an undergraduate research symposium. Undergraduates and their mentors displayed their individual cyanotypes and plant stories alongside their research posters. This represented the interface between science and art during their KBS research experience.

I hosted one public facing workshop at the KBS Bird Sanctuary. During this workshop, a mixture of researchers and non-academic community members came together to share bird stories. These stories were translated into cyanotypes using a mixture of plants and bird features on loan by the bird sanctuary. The large collaborative cyanotype tapestry featured feathers from pheasant, geese, ducks, hawks, owls, and even a few Bald Eagle feathers! This large cyanotype tapestry is on permanent display at the KBS Bird Sanctuary.

Assessment

Both quantitative and qualitative assessments were conducted. Using a playful assessment design, participants were asked to self-assess how their perceptions of being an artist and scientist changed as a result of the workshop.

At UMBS, people placed 15 mL falcon tube caps (a common lab disposable) into a beakers, each representing how they saw themselves as an artist or scientist respectively.

Of the 53 total responses, I found a significant increase in participants seeing themselves as artists after the activity (chi-square test: n=25, p=0.0000267). However, there was no significant difference in people seeing themselves as scientists (chi-square test: n=28, p=0.131). This could be because most workshop participants were researchers and likely already considered themselves to be scientists.

For a qualitative assessment, participants at both UMBS and KBS were asked, “How did this experience change your perception of science and art?”. They wrote their answers on small slips of paper and rolled them into antique dram vials. The responses are pictured below.

Acknowledgements

This would not have been possible without incredible support. At UMBS, Chrissy Billau and Karie Slavik went above and beyond to make this residency possible. At KBS, Liz Schultheis, Nick Haddad, and Nasser Mohammed were absolutely incredible. Additionally, Misty Klotz at the KBS Bird Sanctuary made a wonderful bird-themed cyanotype workshop a reality. I also want to thank my art mentor, Corinne Okada Takara and cousin Jean Brennan, who inspired me to apply to this residency. Thank you.

First cyanotype with Karie Slavik in Douglas Lake

Last cyanotype with Liz Schultheis at the KBS Bird Sanctuary